- Title

-

Rigidity percolation uncovers a structural basis for embryonic tissue phase transitions

- Authors

- Petridou, N.I., Corominas-Murtra, B., Heisenberg, C.P., Hannezo, E.

- Source

- Full text @ Cell

|

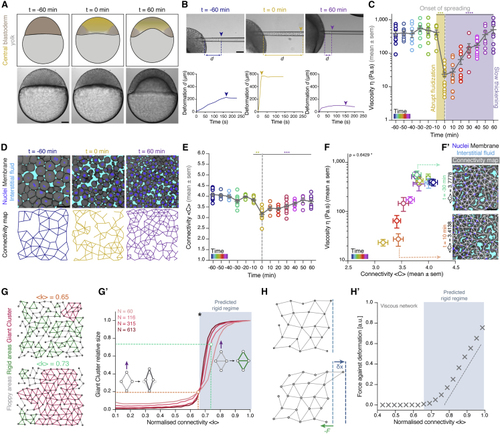

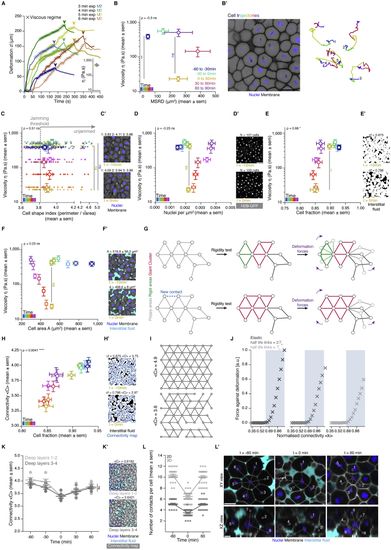

Blastoderm cell connectivity as a potential control parameter of a tissue rigidity percolation transition (A) Schematic representations (top) and bright-field single-plane images (bottom) of an exemplary embryo before (t = −60 min), at the onset (t = 0 min), and after blastoderm spreading (t = 60 min). The yellow-shaded region represents the central blastoderm. (B) Exemplary bright-field images of creep and recovery aspiration experiments in the central blastoderm at the stages described in (A) (top) and corresponding deformation ( (C) Dot plot of individual viscosity values of the central blastoderm obtained from the aspiration experiments shown in (B) overlaid with a line plot of the mean ± SEM as a function of time (color coded for 10 min intervals) (n = 129 embryos, N = 12 embryo batches). Gray dashed line indicates the onset of blastoderm spreading during the fluidization (yellow shade)/thickening (purple shade) process. (D) Exemplary 2D confocal sections at the 1st–2nd deep-cell layer of the blastoderm (top) and their connectivity maps (bottom) at the stages described in (A). Interstitial fluid is marked by dextran, nuclei by H2B-GFP, and membranes by membrane-red fluorescent protein (RFP). (E) Dot plot of individual connectivity <C> values (number of contacts/cell) obtained from central blastoderm confocal sections overlaid with a line plot of the mean ± SEM as a function of time (color coded) (n = 11 embryos for time points −60, −30, 0, 30, and 60 min; n = 6 embryos for all other time points; N = 11 embryo batches). Gray dashed line indicates the onset of blastoderm spreading. (F) Plot of the central blastoderm viscosity values (mean ± SEM) as a function of connectivity <C> (mean ± SEM) over time (color coded as in E; for viscosity n = 129 embryos, N = 12 embryo batches; for connectivity n = 103 blastoderms, N = 11 embryo batches). (F’) Two exemplary blastoderm confocal sections (marked as in D) with overlaid connectivity maps displaying slightly different connectivity, but by an order of magnitude different viscosity values. (G) Exemplary simulated networks with normalized connectivity <k> values above (green line in G’) and below (orange line in G’) the critical point (asterisk in G’) of the rigidity percolation transition. Floppy areas are illustrated in gray, rigid areas in green, and the giant cluster (GC) in red. (G’) Plot of the fraction of the network occupied by the GC as a function of normalized connectivity <k> in simulated random 2D triangular lattices of different sizes (N, number of nodes). The gray-shaded area indicates the network rigid regime above the critical connectivity point (kc, black asterisk). The schematics illustrate how, under the same deformation force (purple arrow), a floppy (left, costing zero energy) or rigid (right, costing non-zero energy due to its central bond) cluster of nodes would deform. (H) Schematic diagram of the force response (F, green arrow) for set deformation (δx, blue arrow) induced by a small displacement of the edge layer of viscous 2D networks. (H’) Plot of the force response illustrated in (H) for viscous 2D networks of size N ∼ 250 nodes, as a function of normalized connectivity <k>. Bond half-life time τ is 2Te, where Te is the number of simulation time steps. The gray-shaded area indicates the rigid regime above the kc, for which viscosity grows linearly as a distance from the critical point. Kruskal-Wallis test (C and E), ρ Spearman correlation test (F). Scale bars: 100 μm in (A) and (B) and 50 μm in (D) and (F’). See also |

|

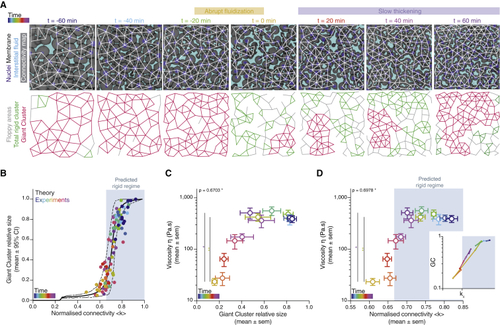

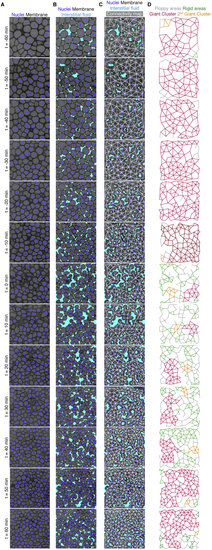

A tissue rigidity percolation transition describes the temporal blastoderm viscosity profile (A) Exemplary 2D confocal sections at the 1st–2nd deep-cell layer of the central blastoderm with overlaid connectivity maps (top) and their rigidity profile (bottom) at consecutive time points during the fluidization/thickening process (color coded). Interstitial fluid is marked by dextran, nuclei by H2B-GFP, and membranes by membrane-RFP. Floppy areas are illustrated in gray, rigid areas in green, and the rigid GC in red. Shaded yellow and purple areas indicate the time period of tissue fluidization and thickening, respectively. (B) Plot of the fraction of the network occupied by the GC (mean ± 95% confidence interval [CI]) as a function of normalized connectivity <k> in simulated random networks of the same size as the average size of experimental networks (black). Overlaid dot plot of the measured GC sizes as a function of the normalized connectivity <k> for experimental networks of the central blastoderm at different time points during the fluidization/thickening process (color coded for 10 min intervals) (n = 103 experimental networks, N = 11 embryo batches), agreeing with the theoretical expectation. (C) Plot of tissue viscosity (mean ± SEM) as a function of the GC relative size (mean ± SEM) for experimental networks of the central blastoderm at different time points during the fluidization/thickening process (color coded as in B) (for viscosity n = 129 embryos, N = 12 embryo batches; for GC n = 103 blastoderms, N = 11 embryo batches). Statistical tests were performed in comparison to t = 0 min. (D) Plot of tissue viscosity (mean ± SEM) as a function of normalized connectivity <k> (mean ± SEM) for the samples described in (C) (for viscosity n = 129 embryos, N = 12 embryo batches; for normalized connectivity <k> n = 103 blastoderms, N = 11 embryo batches). Statistical tests were performed in comparison to t = 0 min. The integrated plot illustrates the time trajectory (color coded) of the central blastoderm material phase state (relative size of GC) as a function of its connectivity (kc). The gray-shaded region in (B) and (D) indicates the rigid regime above the kc. Kruskal-Wallis test (C and D), ρ Spearman correlation test (C and D). Scale bars: 50 μm in (A). See also |

|

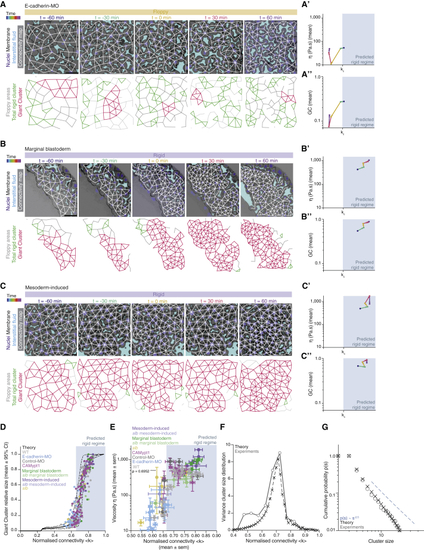

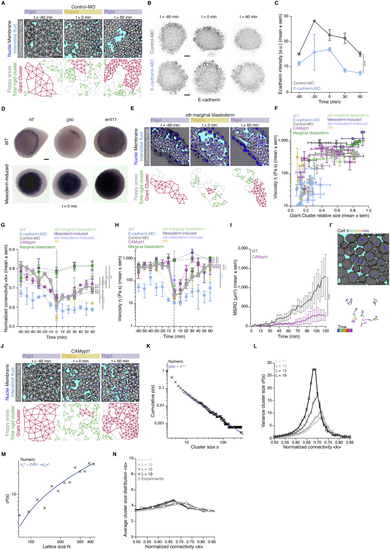

The blastoderm connectivity profile identifies key hallmarks of criticality during its rigidity percolation PT (A–C) Exemplary 2D confocal sections at the 1st–2nd deep-cell layer of the central blastoderm of an (A’, B’, and C’) Plots of the time trajectory (color coded) of blastoderm viscosity (mean) as a function of its normalized connectivity <k> for (A’’, B’’, and C’’) Plots of the time trajectory (color coded) of the GC relative size as a function of its normalized connectivity <k> for the samples described in (A’), (B’), and (C’). (D) Plot of the fraction of the network occupied by the GC (mean ± 95% CI) as a function of normalized connectivity <k> in simulated random networks of the same size as the average size of WT experimental networks (black). Overlaid dot plot of the measured GC size as a function of the normalized network connectivity <k> of the central blastoderm in WT (n = 103, N = 11), (E) Plot of central blastoderm tissue viscosity (mean ± SEM) as a function of normalized connectivity <k> (mean ± SEM) for the experimental networks described in (D) (for viscosity: central blastoderm of WT n = 129, N = 11; (F) Plot of the variance (Var) of the distribution of rigid cluster sizes p(s) other than the GC, as a function of their normalized connectivity <k>, in simulated networks of the same size as the average size of experimental networks (black) and in the experimental networks described in (D) (gray) (except marginal networks), showing divergence at the critical point, with good theory-experiment agreement. (G) Plot of the cumulative distribution of rigid cluster sizes p(s) other than the GC near the critical point. The numerical experiment shows the scaling behavior of cluster size distribution p(s) for networks of arbitrary large size (∼1,200 nodes). The overlaid plot shows the cluster size distribution near criticality for real networks, showing excellent agreement with predictions. The dashed line shows a power-law p(s) ∼ s−2.5. The gray-shaded regions at the plots indicate the rigid regime above the theoretical kc. ρ Spearman correlation test (E). Scale bars: 50 μm in (A)–(C). See also |

|

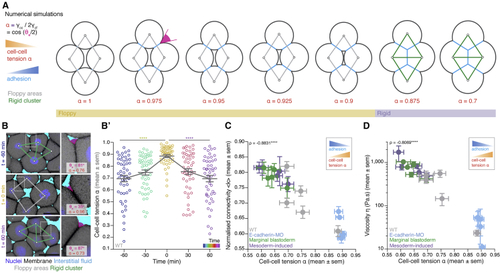

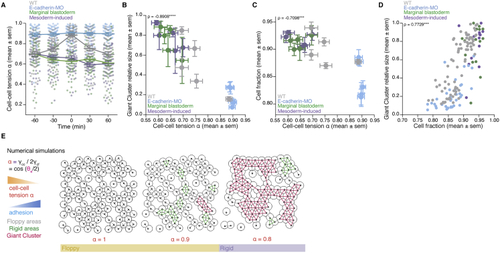

Cell-cell adhesion defines cell connectivity and blastoderm rigidity (A) Numerical simulations of a mechanical toy model for the morphology of a 4-cell rhombus cluster. Increasing cell-cell adhesion (blue) by decreasing cell-cell tension (B) Exemplary high-magnification 2D confocal sections at the 1st–2nd deep-cell layer of the central blastoderm at consecutive time points overlaid with their rigidity profile during the fluidization/thickening process, with close-ups of exemplary contact angle (B’) Dot plot of individual cell-cell tension (C) Plot of normalized connectivity <k> (mean ± SEM) as a function of cell-cell tension (D) Plot of viscosity (mean ± SEM) as a function of cell-cell tension Kruskal-Wallis test (B’), ρ Spearman correlation test (C and D). Scale bars: 20 μm in (B). See also |

|

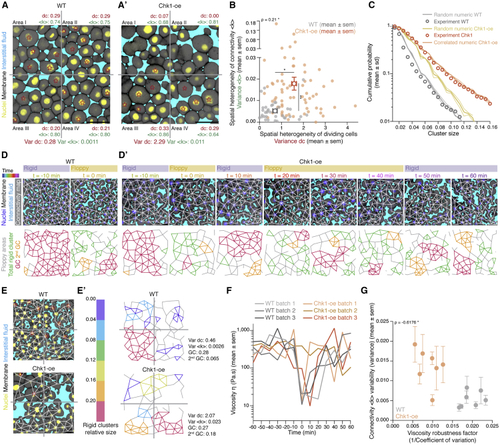

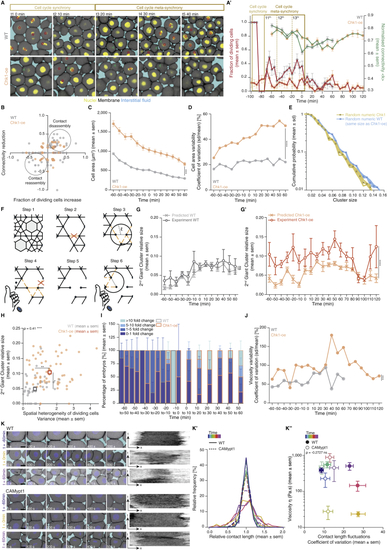

Uniformity in blastoderm rigidity transition relies on meta-synchronous cell divisions generating random cell connectivity changes (A and A’) Exemplary 2D confocal sections at the 1st–2nd deep-cell layer of the central blastoderm of a WT (A) and a Chk1-overexpressing (Chk1-oe, A’) embryo during the last round of meta-synchronous cell cleavages. Interstitial fluid is marked by dextran, nuclei by H2B-GFP, and membranes by membrane-RFP. The Var for the fraction of dividing cells (red stars, (B) Plot of the spatial heterogeneity in connectivity as a function of the spatial heterogeneity in the fraction of dividing cells, expressed as the Var in < (C) Plot of the distribution of rigid cluster sizes p(s) other than the GC for all range of connectivity values in (i) WT and Chk1-oe experimental networks (circles), (ii) simulated random networks with size distribution identical to the experimental ones (WT, shaded gray; Chk1-oe, shaded yellow), and (iii) simulated correlated networks with size distribution identical to the experimental Chk1-oe (shaded orange) (WT n = 103 networks, N = 11 batches, Chk1-oe n = 95 networks, N = 5 batches), showing that Chk1-oe cluster size distribution is wider than the one expected from a model random network, but displays a very good fit if the model network shows spatial correlations in division/bond loss. (D and D’) Exemplary 2D confocal sections at the 1st–2nd deep-cell layer of the central blastoderm of a WT (D) and a Chk1-oe (D’) embryo with overlaid connectivity maps (top) and their rigidity profile (bottom) at different time points during the fluidization/thickening process (color coded), marked as in (A). Floppy areas are illustrated in gray, rigid areas in green, the 2nd GC in orange, and the GC in red. Yellow- and purple-shaded areas indicate floppy and rigid blastoderms, respectively, as judged by the GC relative size. (E) Exemplary 2D confocal sections at the 1st-2nd deep-cell layer of the central blastoderm of a WT (top) and a Chk1-oe (bottom) embryo, marked as in (D), at a fluidized state with marked mitotic cells (red stars) and overlaid connectivity maps. (E’) Their rigidity profile is color coded for the size of the rigid clusters (fraction occupied in the total network). (F) Plot of blastoderm tissue viscosity as a function of time for measurements from 3 independent embryo batches of WT (showing synchronous fluidization) and Chk1-oe (showing heterogeneous phases of fluidization/thickening) embryos. (G) Plot of normalized connectivity <k> variability, expressed as the Var in normalized connectivity <k> between the quadrants (mean ± SEM) shown in (A) and (A’) as a function of a robustness viscosity factor, expressed as the inverse of coefficient of Var between the viscosity measurements (see Kruskal-Wallis test (B), ρ Spearman correlation test (B and G). Scale bars: 50 μm in (A), (A’), (D), (D’), and (E). See also |

|

Temporal analysis of blastoderm viscosity and underlying cellular dynamics, related to ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Kruskal-Wallis test (B, C), Mann-Whitney test (D-F, H), ρ Spearman correlation (B-F, H). Scale bars, 50 μm (B’, D’, E’, H’, K’), 20 μm (C’, F’, L’). |

|

Rigidity analysis in WT embryos, related to ( ( ( ( |

|

Experimental manipulations of connectivity, topological rigidity, and tissue viscosity, related to ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Kruskal-Wallis test (G, H), Mann-Whitney test (C, I). Scale bars, 50 μm (A, B, E, I’, J), 100 μm (D). |

|

|

|

Effects of Chk1 overexpression in cellular, topological, and material properties of the zebrafish blastoderm and role of cell contact length fluctuations on tissue viscosity, related to ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Kruskal-Wallis test (G’, H), Mann-Whitney test (C, D, J), ρ Spearman correlation (H, K’’). Scale bars, 20 μm (A) 10 μm (K). |

Reprinted from Cell, 184(7), Petridou, N.I., Corominas-Murtra, B., Heisenberg, C.P., Hannezo, E., Rigidity percolation uncovers a structural basis for embryonic tissue phase transitions, 1914-1928.e19, Copyright (2021) with permission from Elsevier. Full text @ Cell