- Title

-

Habitual Daily Intake of Fried Foods Raises Transgenerational Inheritance Risk of Heart Failure Through NOTCH1-Triggered Apoptosis

- Authors

- Wang, A., Wan, X., Zhu, F., Liu, H., Song, X., Huang, Y., Zhu, L., Ao, Y., Zeng, J., Wang, B., Wu, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, J., Yao, W., Li, H., Zhuang, P., Jiao, J., Zhang, Y.

- Source

- Full text @ Research (Wash D C)

|

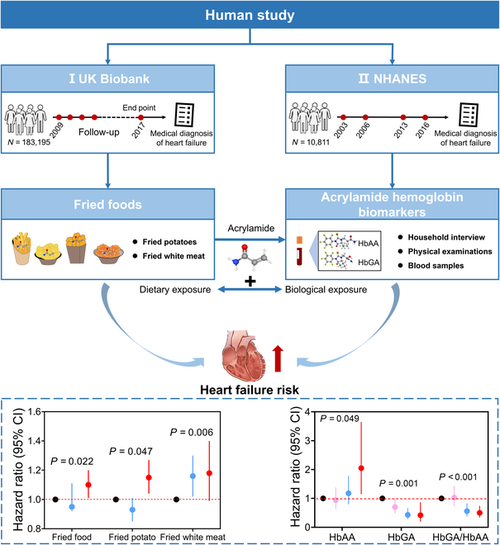

Study design and outcomes for the associations of fried food consumption or hemoglobin biomarkers of acrylamide with the risk of HF in the UK Biobank and NHANES. |

|

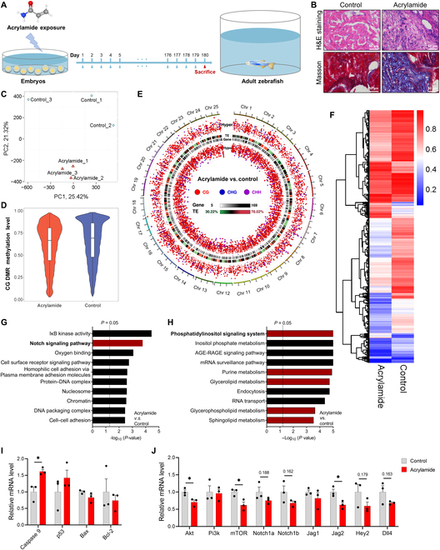

Chronic exposure to acrylamide induces HF in adult zebrafish. (A) Experimental design: embryos at 2 hpf exposed to 0.25 mM acrylamide for 180 d. (B) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson staining of adult zebrafish heart sections in control and acrylamide treatment (0.25 mM) groups. (C) The control and acrylamide-treated groups were completely distinguished by different colors in principal components analysis (PCA) plots based on WGBS analysis. (D) The global methylation level between the control and acrylamide-treated groups based on WGBS analysis. (E) Global methylation patterns in zebrafish hearts exposed to 0.25 mM acrylamide. (F) Heatmap showing differentially methylated changes in heart tissue between control and acrylamide-treated zebrafish based on CG pattern. (G and H) GO and KEGG analyses of WGBS data. (I) Relative mRNA expression of cardiac-apoptosis-related genes in control and acrylamide-treated zebrafish (n = 3 per group). (J) Relative mRNA expression of cardiac NOTCH and PI3K/AKT-related genes in control and acrylamide-treated zebrafish (n = 3 per group). Data are presented as the means ± SEM. Significance was calculated using 2-tailed P values by unpaired Student’s t test; *P < 0.05. |

|

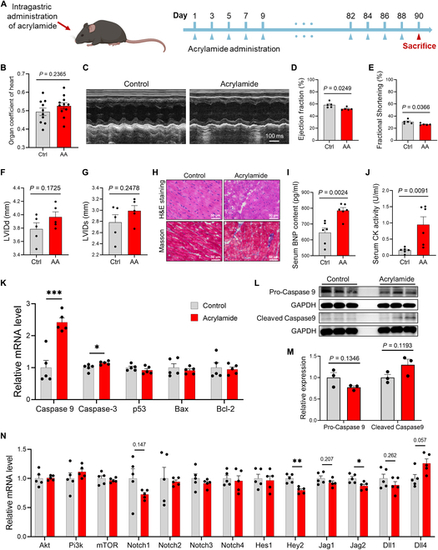

Chronic exposure to acrylamide exposure induces HF in mice. (A) Experimental design: 8-week-old mice exposed to acrylamide (0.5 mg/kg·bw per day) for 90 d. (B) The organ coefficient of the heart in control and acrylamide treatment groups. (C) Representative M-mode echocardiogram in control and acrylamide treatment groups. (D) Ejection fraction (%), (E) fractional shortening (%), (F) left ventricular internal dimension diastole (LVIDd) (in millimeters), and (G) left ventricular internal dimension systole (LVIDs) (in millimeters) based on echocardiogram results in control and acrylamide (AA) treatment groups (n = 5 per group). (H) Representative images of H&E and Masson staining of mouse heart sections in control and acrylamide treatment groups (0.5 mg/kg·bw per day). (I) Serum BNP level and (J) serum CK level in control and acrylamide treatment groups (n = 6 per group). (K to M) Relative mRNA expression of cardiac apoptosis-related genes and proteins in control and acrylamide-treated mice (n = 5 per group for quantitative polymerase chain reaction and n = 3 per group for Western blotting). (N) Relative mRNA expression of cardiac NOTCH and PI3K/AKT-related genes in control and acrylamide-treated mice (n = 5 per group). Data are presented as the means ± SEM. Significance was calculated using 2-tailed P values by unpaired Student’s t test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. |

|

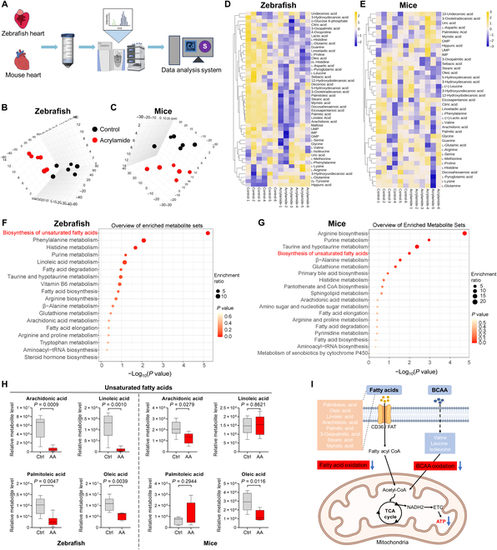

Chronic exposure to acrylamide induces mitochondria dysfunction and metabolic remodeling based on metabolomics analysis in zebrafish and mice. (A) Schematic diagram of metabolomics for the isolated hearts from both zebrafish and mice. (B and C) 3-dimensional PCA scores plots of metabolites profiles of hearts from zebrafish and mice exposed to acrylamide, respectively (n = 6 per group). (D and E) Heatmap of metabolites based on the normalized mass spectrometry intensity in hearts of zebrafish and mice, respectively. (F and G) KEGG pathway analysis of differential metabolites in hearts of zebrafish and mice, respectively. (H) The relative unsaturated fatty acids levels in hearts of zebrafish and mice, respectively. (I) Model of cardiac mitochondrial energy metabolism disturbance induced by chronic acrylamide exposure. The illustration was created using BioRender. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. Significance was calculated using 2-tailed P values by unpaired Student’s t test. m/z, mass/charge ratio; CoA, coenzyme A; UMP, uridine monophosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate; BCAA, branched-chain amino acid; NADH2, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2; ETC, electron transfer chain; TCA, tricarboxylic acid. PHENOTYPE:

|

|

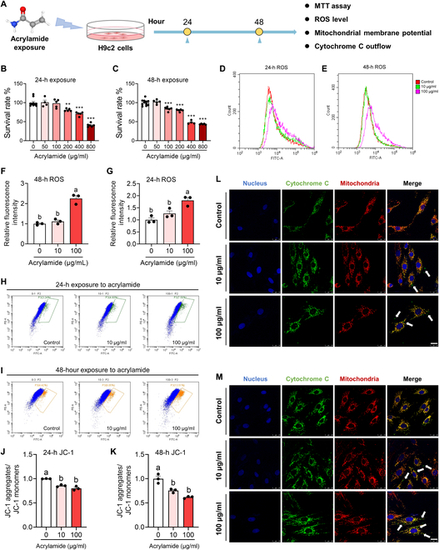

Acrylamide induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis with ROS accumulation, cytochrome C outflow, and dropped mitochondrial membrane potential in H9c2 cells. (A) Schematic diagram of cell study. (B and C) Survival rates of H9c2 cells after 24- and 48-h acrylamide exposure, respectively. The viability of cells was determined by the 3-(4,5)-dimethylthiahiazo (-z-y1)-3,5-di-phenytetrazoliumromide (MTT) assay. (D and E) Accumulation of ROS was observed at 24 and 48 h by 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe after acrylamide treatment. (F and G) Quantification of ROS accumulation in H9c2 cells after 24- and 48-h acrylamide exposure, respectively (n = 3 per group). (H and I) Mitochondrial membrane potential was evaluated at 24 and 48 h by JC-1 probe after acrylamide treatment. (J and K) Quantification of mitochondrial membrane potential in H9c2 cells after 24- and 48-h acrylamide exposure, respectively (n = 3 per group). (L and M) Cytochrome C outflow was observed by colocalizing mitochondria (red) and cytochrome C (green) fluorescently, while cell nucleus was dyed by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) with acrylamide exposure for 24 and 48 h, respectively. The white arrows point out the occurrence of cytochrome C outflow. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. Significance was calculated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001; groups labeled with different letters differed significantly (P < 0.05). FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. |

|

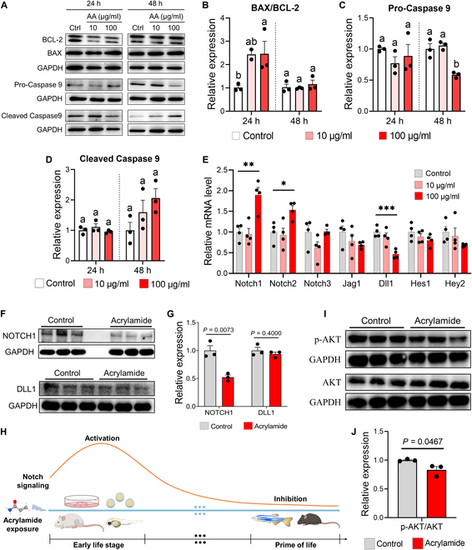

Acrylamide induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis via NOTCH-PI3K/AKT signaling in H9c2 cells. (A to D) Western blotting of apoptotic pathway related proteins (BCL-2, BAX, pro-Caspase 9, and cleaved Caspase 9) shows that acrylamide treatment activates apoptotic pathway in H9c2 cells (n = 3 per group). (E) Relative mRNA expression of NOTCH signaling pathway-related genes in H9c2 cells with acrylamide treatment for 48 h (n = 4 per group). (F and G) Western blotting of NOTCH1 and DLL1 proteins shows that acrylamide treatment inhibits NOTCH signaling pathway in heart of 5-month-old mice (n = 3 per group). (H) Schematic diagram of NOTCH signaling changes with acrylamide exposure. (I and J) Western blotting of p-AKT and AKT proteins shows that acrylamide treatment inhibits PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in heart of mice (n = 3 per group). Data are presented as the means ± SEM. Significance was calculated using 2-tailed P values by unpaired Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001; groups labeled with different letters differed significantly (P < 0.05). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. |

|

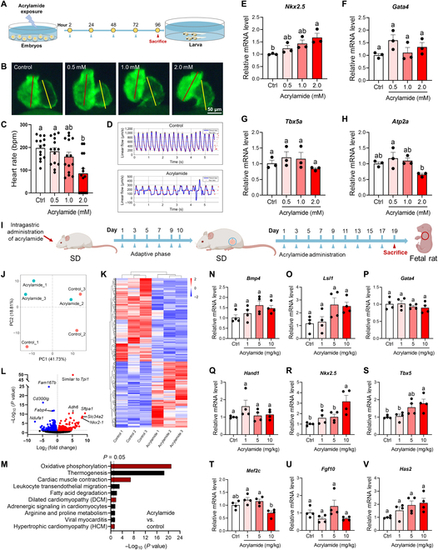

Acrylamide disturbs heart development during early life stage in both zebrafish embryos and rat embryos. (A) Experimental design: embryos exposed to acrylamide (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM) from 2 to 96 hpf. (B) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of Tg(cmlc2: GFP) zebrafish embryos with green fluorescent protein specifically expressed in the myocardial cells. Embryos at 2 hpf were exposed to acrylamide (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM) for 4 d. (C) Heart rates were measured in zebrafish (2 hpf) treated with acrylamide for 4 d (n = 20 per group). (D) Blood flow dynamics map in control and acrylamide-treated (2.0 mM) zebrafish. (E to H) Relative mRNA expression of cardiac-development-related genes in control and acrylamide-treated zebrafish (n = 3 per group). (I) Experimental design: pregnant rat exposed to acrylamide (1, 5, and 10 mg/kg·bw per day) for 19 d. (J) PCA scores plots based on RNA-seq data of hearts from rat embryos exposed to acrylamide (10 mg/kg·bw per day) (n = 3 per group). (K) Cluster analysis and (L) volcano plot of differentially expressed genes based on RNA-seq analysis. (M) KEGG analysis of RNA-seq data. (N to V) Relative mRNA levels of cardiac-development-related genes in control and acrylamide-treated rat embryos (n = 4 per group). Data are presented as the means ± SEM. Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; groups labeled with different letters differed significantly (P < 0.05). |

|

Acrylamide exposures generates epigenetic variations via DNA methylation. (A) Relative mRNA expression of cardiac NOTCH signaling pathway related genes in control and acrylamide-treated (10 mg/kg·bw per day) rat embryos (n = 3 per group). Relative mRNA expression of cardiac Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b genes in control and acrylamide-treated (1, 5, and 10 mg/kg·bw per day) rat embryos at (B to D) GD8 (n = 5 per group), (E to G) GD12 (n = 4 per group), and (H to J) GD19 (n = 6 per group). (K) Molecular docking results and residues of acrylamide interacting with DNMT1. (L) Acrylamide–DNMT1 conformational changes during the MD simulation: P1224 and C1226 are in the left, and E1266 and R1312 are in the right. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. Significance was calculated using 2-tailed P values by unpaired Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01; groups labeled with different letters differed significantly (P < 0.05). |

|

Main findings of this study. Briefly, this study demonstrates that frequent fried food consumption is strongly associated with higher HF risk due to the harmful effect of acrylamide in fried foods. The results reveal that long-term exposure to acrylamide induces HF through mitochondria disorder and NOTCH1-triggered apoptosis. |