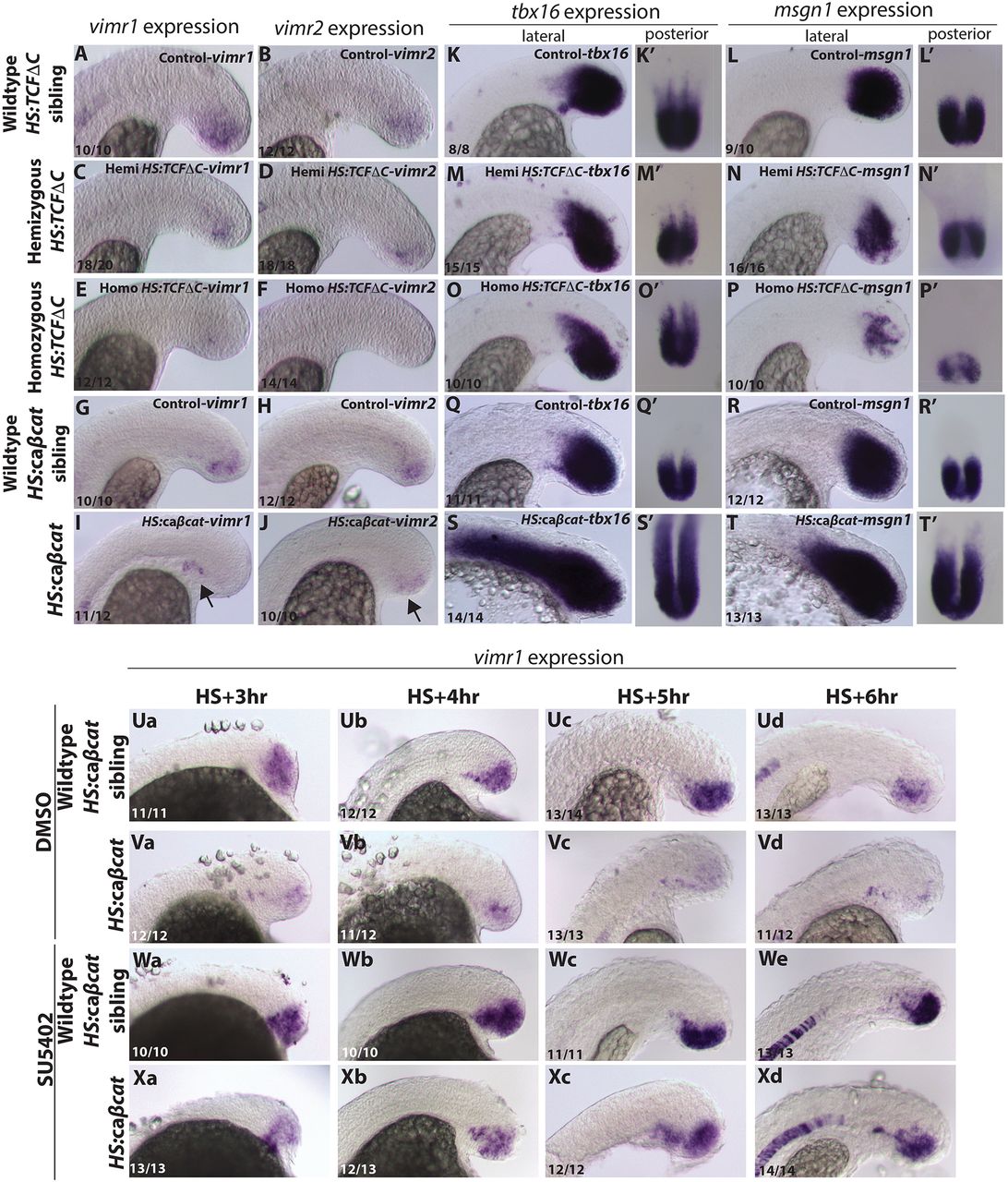

Fig. 6

Wnt promotes EMT initiation and cooperates with FGF to promote EMT termination in tailbud NMPs. (A-F) vimr1 and vimr2 expression was analyzed in 20-somite stage wild-type sibling (A,B), hemizygous HS:TCFΔC (C,D) and homozygous HS:TCFΔC (E,F) embryos. Wnt inhibition leads to the loss of vimr1 and vimr2. (G-J) Expression of vimr1 and vimr2 was also analyzed in HS:caβ-catenin embryos (I,J) and their wild-type siblings (G,H). Wnt overactivation leads to a loss of vimr1 and vimr2 expression and a shift towards the ventral anterior portion of the tailbud (black arrow in I,J). (K-T′) tbx16 and msgn1 expression was examined in control (K-L′,Q-R′), hemizygous HS:TCFΔC (M-N′), homozygous HS:TCFΔC (O-P′) and HS:caβ-catenin (S-T′) embryos. Wnt inhibition had little effect on tbx16 expression but led to decreased expression of msgn1. Wnt overactivation led to expansion of the tbx16 and msgn1 expression domains. (Ua-Xd) Epistasis experiments were performed to examine the control of vimr1 expression by the Wnt and FGF signaling pathways. HS:caβ-catenin embryos were heat shocked at the 12-somite stage and treated with SU5402 or vehicle only (DMSO). These embryos were subsequently fixed 3 h, 4 h, 5 h and 6 h after heat shock induction for in situ hybridization. DMSO-treated control embryos exhibited consistent expression of vimr1 during somitogenesis (Ua-d), whereas DMSO-treated HS:caβ-catenin embryos had decreased expression of the EMT marker in the tailbud (Va-d). Consistent with previous data (Fig. 3), FGF inhibitor-treated embryos had increased expression of vimr1 (Wa-d). HS:caβ-catenin embryos in the presence of SU5402 maintained strong expression of vimr1 (Xa-d). All tailbud images are lateral views, except where indicated otherwise.