- Title

-

Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Physalis alkekengi L. Extracts In Vitro and In Vivo: Potential Application for Skin Care

- Authors

- He, B.W., Wang, F.F., Qu, L.P.

- Source

- Full text @ Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med.

|

Flow chart for the extraction of |

|

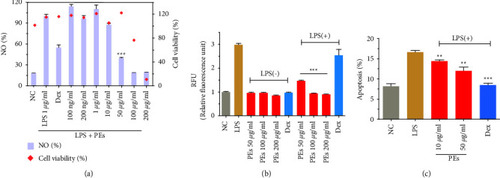

Quantification of NO production and cell viability (a), NOS activities (b), and cell apoptosis (c) in RAW264.7. PEs at different concentrations were incubated with cells for 1 h prior to incubation with LPS (1 |

|

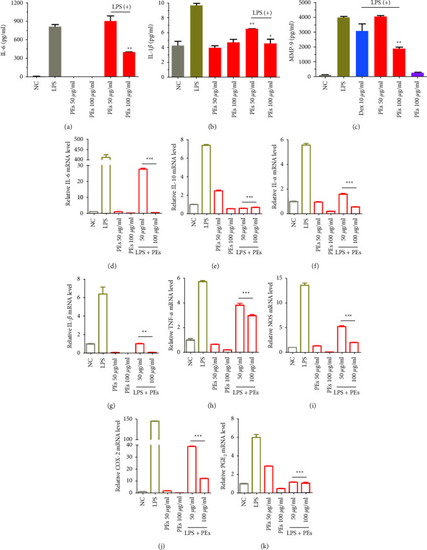

Anti-inflammatory effects of PEs on LPS-stimulated RAW264.7. Cells were pretreated with PEs at the concentrations of 50, 100 |

|

Antisenescent effect of PEs on HFF-1. Cells were treated with 20 mg/mL of D-gal together with 100 ng/mL of PEs for 72 h. After, cells were stained according to the manufacturer's protocol. |

|

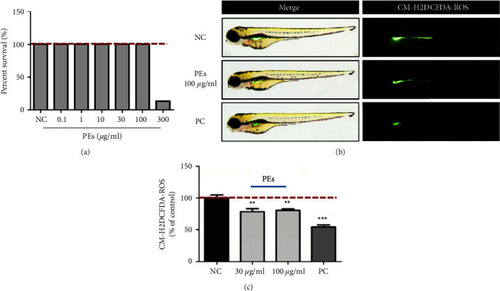

Antioxidant effect of PEs |

|

Anti-inflammatory effect of PEs against CuSO4-induced inflammation |

|

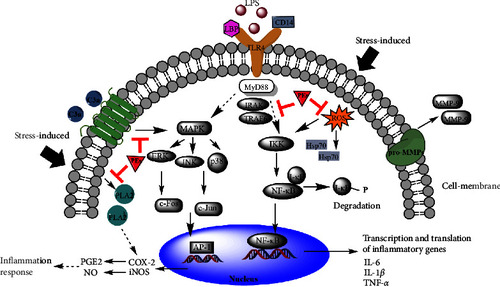

Proposed roles of PEs in the suppression of LPS-induced and oxidative stress-induced inflammatory pathways. |