- Title

-

Social Experience Regulates Endocannabinoids Modulation of Zebrafish Motor Behaviors

- Authors

- Orr, S.A., Ahn, S., Park, C., Miller, T.H., Kassai, M., Issa, F.A.

- Source

- Full text @ Front. Behav. Neurosci.

|

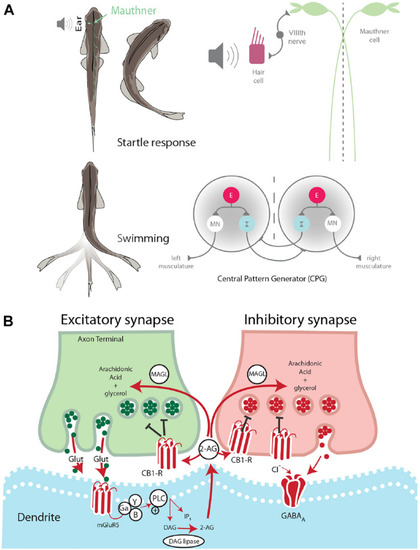

Startle escape and swim motor behaviors are socially regulated. |

|

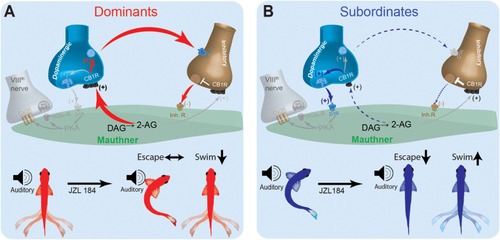

Endocannabinoid signaling pathway is socially regulated and its modulation of M-cell excitability is status-dependent. |

|

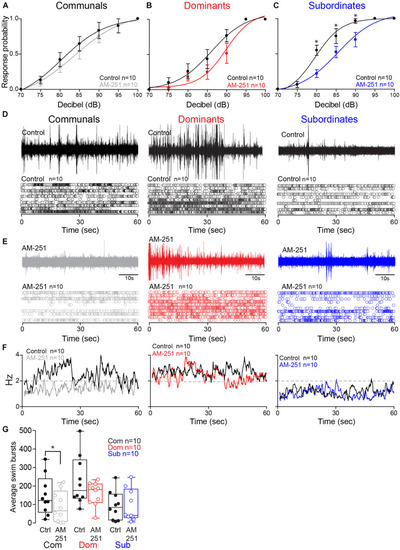

2-AG modulation of escape and swimming activities is social status-dependent. |

|

Effect of AM-251 on status-dependent escape probability and swim frequency. |

|

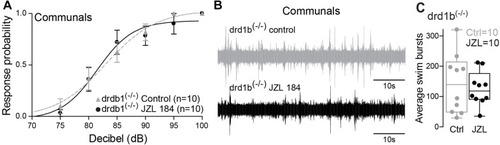

drd1b expression is socially regulated and necessary for status-dependent ECS regulation of escape and swim circuits. |

|

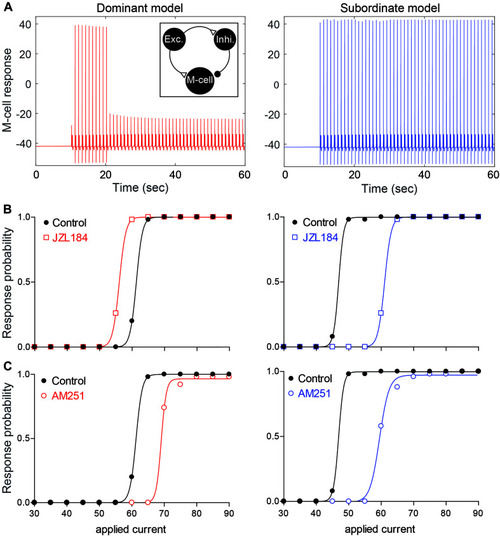

Neurocomputational models simulating the effects of 2-AG on the escape response. |

|

Schematic model for social status-dependent regulation of neurochemical inputs to the M-cell: The M-cell (green) receives inputs from DA cells (blue), the excitatory VIIIth cranial nerve (gray), and inhibitory (brown). Our model predicts distinct neurochemical pathways in dominants |