- Title

-

Understanding the development of tuberculous granulomas: insights into host protection and pathogenesis, a review in humans and animals

- Authors

- Lyu, J., Narum, D.E., Baldwin, S.L., Larsen, S.E., Bai, X., Griffith, D.E., Dartois, V., Naidoo, T., Steyn, A.J.C., Coler, R.N., Chan, E.D.

- Source

- Full text @ Front Immunol

|

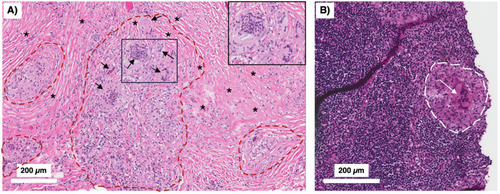

Human TB granulomas may be non-necrotic or necrotic. Several different fates of granulomas occur and such heterogeneity may present in the same individual. |

|

Peritoneal TB with non-necrotizing granulomas. A 51-year-old man from the Philippines presented with a two-year history of early satiety, intractable abdominal pain, and weight loss exceeding 60 pounds. Abdominal CT showed evidence of “peritoneal carcinomatosis.” |

|

Formation of foamy macrophages and their role in TB pathogenesis. Foamy macrophages play a key role in the formation of caseous necrosis. They are formed when macrophages acquire cholesterol-containing LDL particles into lipid bodies. See text for discussion. ESAT-6, 6 kDa early secretory antigenic target; GPR109A, a specific G-protein coupled receptor; LB, lipid bodies; LDL, low density lipoprotein; MA, mycolic acids; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-gamma; TR4, testicular receiver 4. |

|

Mechanisms by which deficiency or excess CD4+IFNγ+ T cells predispose to TB. |

|

Differential expression of hypoxia, HIF-1α, and downstream effects in the central and peripheral regions of the necrotic granuloma. The central region of a necrotic granuloma is more hypoxic. As a result, there is greater HIF-1α expression with a panoply of downstream effects due to HIF-1 activity. One immune mechanism induced by HIF-1 is aerobic glycolysis, which in turn induces autophagy through the byproduct lactate. Hence, the central necrotic area of an intact human TB granuloma is usually sterile or with low bacterial burden. In contrast, the peripheral region of the granuloma less hypoxic with less HIF-1α induction. In the presence of macrophages that are less effective in killing |

|

Either excessive or deficiency of molecular or cellular immune elements may predispose to unprotective granuloma or defense against |

|

Relative IDO-1 activity helps dictate the level of protection by TB granulomas. IDO-1 activity can also be an indicator of the protectiveness of a granuloma. When there is an optimal level of IDO-1 inhibition, the remodeling of the granulomas allows access of CD4+ T cells to the central core of the granuloma, resulting in |

|

Origin of |

|

Distribution of lesions in primary and post primary TB. The localization of lesions of |

|

Anatomical-physiological-chemical mechanisms by which post-primary TB is more common in the upper lobes of the lungs. Based on differences in the physiological-chemical properties between the upper lobes and lower lobes, primary |

|

Different types of TB lung lesions in the C3HeB/FeJ mice. Three types of histopathologic TB lesions are seen in the C3HeB/FeJ mice. |