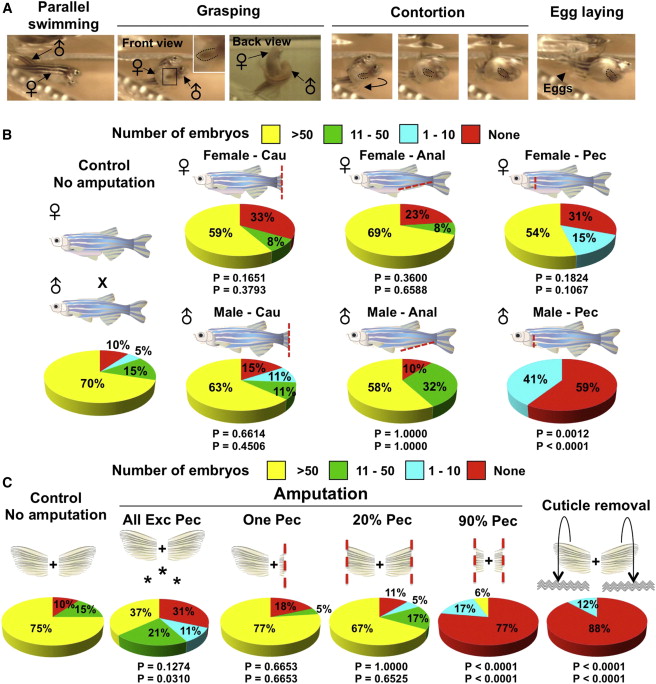

Fig. 2

Male Pectoral Fins and ETs Are Important Breeding Structures

(A) Still images of zebrafish mating behavior acquired by high-speed video. In the parallel swimming image, the male chases the female and attempts to align in a parallel position. In the grasping images, the male positions one of his pectoral fins below the female abdomen, while placing his posterior trunk over that of the female. In the contortion images, the male bends his body, arching away from the female. In the egg laying image, these activities by the male stimulate egg release (arrowhead). Inset, enlargement of male pectoral fin. Dotted lines indicate male pectoral fin.

(B) Pie charts of mating test after complete fin amputations as indicated in cartoons. Cau, Anal, and Pec indicate full (>90%) amputation of caudal, anal, and pectoral fins, respectively. n = 12 to 22 animals. The top p value is calculated from Fisher’s exact test between the “no amputation” control and the experimental group for the percentage of successful matings, with one or more embryos considered successful (none versus more than one embryo). The bottom p value is calculated from Fisher’s exact test between the no-amputation control and the experimental group for the percentage of successful matings, with ten or more embryos considered successful (zero to ten embryos versus more than ten embryos). As zebrafish typically have 50–200 embryos per mating, a clutch size of one to ten embryos is unusually small and of borderline success.

(C) Pie charts showing results of mating tests after various fin injuries, indicated by the cartoons above the charts, were given to male zebrafish. Asterisks denote experiments in which all fins except pectoral fins were amputated. n = 17 to 22 animals.

Reprinted from Developmental Cell, 27(1), Kang, J., Nachtrab, G., and Poss, K.D., Local dkk1 crosstalk from breeding ornaments impedes regeneration of injured male zebrafish fins, 19-31, Copyright (2013) with permission from Elsevier. Full text @ Dev. Cell